The Connecting Medieval Music project provides a platform for the study of contrafacta in medieval Romance lyric. It is a digital repertory of Occitan and French models and contrafacta, which also includes all Latin, German, Italian, and Galician-Portuguese contrafacta connected to the Gallo-Romance tradition.

Thanks to its interactive interface, Connecting Medieval Music invites users to explore the connections between lyrics across Europe in their geographical and chronological dimensions.

The project does not only consist of a list of known cases of contrafaction but aims to provide information on the formal and cultural features of each lyric: the circumstances of its compositions, the people involved, the events it mentions, the sources that preserve it, and much more. People, places, events, lyrics, and manuscripts are all linked in an interconnected network that reproduces a layer of Europe's cultural history.

Contrafacta: definition and criteria

While the term "contrafactum" is well-known in modern scholarship, it is important to clarify how this concept is applied within the context of this project. "Contrafactum" refers to the practice of reusing an existing melody for a new text—a technique that was extremely popular during the Middle Ages. The new text usually replicated the syllabic structure and often the rhyme scheme and sounds of the original model. These formal features can be likened to the "fossils" left by melodies, helping us identify a contrafactum in cases where the musical notation is irretrievably lost, as is true for many medieval vernacular lyrics. It would have been possible to adopt a "skeptical" definition, applying the status of contrafactum only to works that have survived with music, since only through a direct comparison of the melodies can the musical match be verified. However, this approach is ultimately not viable, as a contrafactum does not cease to exist simply because the last surviving copy of its melody is lost or the last bearer of its oral tradition dies or forgets it. When analyzing a phenomenon that is inherently fragmentary—a condition common to all medieval research—it is not feasible to restrict the study to items that have survived intact. This is evident when we consider the Troubadour tradition, where there are only four known cases in which both the original model and its contrafactum have survived with their music. If we were to limit our discussion of contrafaction to these few instances, we would be compelled to argue that contrafacta were virtually non-existent among Occitan poets—despite knowing that contrafaction was, in fact, a fundamental practice in Troubadour lyric production.

Another possible approach, favored by those primarily focused on the metrical aspects of medieval lyrics, is to consider contrafacta only cases where texts share identical metrical structures. This perspective, however, overlooks the musical nature of contrafaction and fails to account for the flexibility with which music can adapt to texts with differing syllabic counts. Therefore, our definition of contrafactum includes "imperfect contrafacta," where lyrics modify the structure of the model but still reuse a substantial portion of the original melody without fundamentally altering its integrity. Such modifications might involve changes in the number of lines per stanza, the number of syllables per line, or the type of rhymes. This category is distinct from "intermelodicity," which involves reusing smaller segments of a melody, integrating them into a new musical context, reconfiguring its modules into a new structure, or significantly altering the original. While intermelodic connections are indicated in our research, much like intertextual relationships, they are not categorized as contrafacta.

The aim of this project is to encourage the study of contrafaction, not to establish a fixed canon. Connecting Medieval Music designed to serve not only as a tool for literary and musicological analysis but also as a means of connecting the threads of musical and poetic culture in the European Middle Ages. From this perspective, it is clear that an inclusive approach is more likely to yield meaningful results. We take on the responsibility of analyzing and discussing cases of contrafaction that have not survived with their music. Additionally, we include in our database cases that display metrical affinities and lyrics that have been considered contrafacta, even when we contend that they do not fit this definition, thereby engaging critically with previous scholarship.

Connecting Medieval Music... to what?

In the database, you will find much more than just contrafacta. This project aims to link medieval songs that share the same music and to describe—or at least indicate—the literary implications of these musical connections. It also seeks to situate these musical practices within their broader cultural and historical contexts: the people involved or mentioned in these texts, the manuscript sources in which they are preserved, and other related literary works. Each of these elements has its own story, contributing to the cultural networks we are attempting to reconstruct.

Different visualizations for different research

The map visualization can be customized to display different types of information depending on specific research goals. By default, only green pins are shown on the map. These represent "Creation events," indicating the location where a model, a contrafactum, or a song with metrical affinities was composed. Clicking on a green pin reveals the network connecting the model and its contrafacta. Clicking on this pin provides access to detailed information about the work.

Clicking on the Filter icon the left sidebar, it is possible to change the visualized entities by selecting one or more of the following checkboxes:

![]() Creations of literary works: displays all the place of composition of works, including those which are not models or contrafacta.

Creations of literary works: displays all the place of composition of works, including those which are not models or contrafacta.

![]() Productions of manuscript sources: places of production of manuscript sources.

Productions of manuscript sources: places of production of manuscript sources.

![]() Authors' activity: displays all places associated with any event related to the life of the authors.

Authors' activity: displays all places associated with any event related to the life of the authors.

![]() Other historical events: displays all biographical, political, military, religious, events that are linked to any entity in the database.

Other historical events: displays all biographical, political, military, religious, events that are linked to any entity in the database.

Manuscript sources

All sources can be searched using their full shelfmark (e.g., "Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, fr. 865"). The main songbooks of the Romance tradition are also identified by the sigla that denote them within their respective repertories. Scholars should be aware that the same siglum can refer to different manuscripts depending on the repertory (i.e., the language of the text involved) and that the same manuscript may have different sigla across various repertories (usually corresponding to distinct sections within a miscellaneous or composite source). A full list of manuscripts can be found on the Sources page. .

Time-Spans

Rarely in medieval studies can we assign an event to a precise point in time. More often, we can only provide broad or hypothetical time-spans (e.g., “early 13th century,” “middle of the 13th century,” “between 1194 and 1198”). In such cases, it is necessary to adopt reasonable conventions to translate these vague indications into machine-readable dates, which allows for a functional timeline widget.

When the indications are vague, we use arbitrary yet sensible and consistent numeric translations. For example:

- “Beginning of the 13th century” is translated as 1201–1210

- “End of the 13th century” is translated as 1291–1300

- “Between the 12th and the 13th century” is translated as 1191–1220

- “Middle of the 13th century” is translated as 1226–1275

If there are multiple hypotheses about the composition date, we translate this into the most inclusive range. For instance, “after 1194 and before 1198, around 1196” will be visible during any time that the timeline cursor is between 1194 and 1198.

As a result, certain events that are believed to occur over a relatively short period (such as the creation of a song or the production of a manuscript) might occupy a broader time span. These events remain visible throughout the entire time span during which their occurrence is considered plausible.

Spelling

The fluctuating nature of medieval spelling presents a challenge for a digital project and its users. To address this, we have adhered to widely accepted standards to ensure that users can effectively find what they are looking for.

Lyrics

For the incipits of the lyrics, the spelling follows that of the bibliographic repertories relevant to each corpus, with modifications made only when absolutely necessary. However, it is common practice among medieval scholars to refer to repertory numbers, which provide unambiguous identifiers. It is recommended to use these identifiers when referring to or searching for a specific lyric. The repertories for both incipits and IDs are:

Occitan: BEdT

French: Linker

Galician-Portuguese: LPGP and CSM

German: MF

Conducti: CPI

This project occasionally incorporates works from other repertories, including liturgical works (Cantus) and the contrafacta found in the Jeu de Saint'Agnès (SA).

People and Places

As a general rule, names of people and places are given in their original language. Authors' names follow the spelling used in the aforementioned repertories whenever possible. The project employs "Appellations," which record different spellings, nicknames, and alternative ways of referring to a person or entity, including senhals and periphrasis. For a complete list of available entities, please visit the People and Places pages.

Main bibliographic sources

The information available on Connecting Medieval Music comes from hundreds of sources, but the foundational basis for the Occitan repertory is the BEdT, which provides accurate information on the metrical relationships, place and date of composition of Occitan lyrics. We have followed BEdT, except where more recent research was available. The more useful resource for the integration of notices on troubadours was the Dizionario biografico dei trovatori (Guida - Larghi 2014). Linker 1979, checked against the bibliography by Raynaud - Spanke 1955, constituted the basis for the information regarding the French repertory.

As with all research on contrafacta in medieval Romance lyrics, this project is built upon the foundational works by Friedrich Gennrich and Hans Spanke.

A full list of the cited scholarly works is available on the Bibliography page. References regarding single items (works, people etc.) are specified at the bottom of the sidebar.

The digital platform

The Connecting Medieval Music platform uses MedMus – DH-DW extension for medieval music, literature, and cultural heritage, created by Stefano Milonia.

DH-DW (Digital Humanities-Data Workbench) is a Drupal-based software created by Steve Ranford (University of Warwick) and Steven Jones (ComputerMinds), first built for the project Oiko.world, directed by professor Micheal Scott.

The MedMus platform has also been adopted by the project Prosopographical Atlas of Romance Literature, with which we have had a data-sharing agreement.

Music transcriptions

The musical transcriptions, available for the Occitan repertoire and for a small number of French works, are embedded from MedMel: The Music of Medieval Vernacular Lyric – Connecting Medieval Music's sister project.

By clicking on the MedMel icon, you can view the full transcription on the MedMel website. Here, you’ll have access to the edition’s advanced features, including:

- Transcription in square (or Messine) notation

- The facsimile

- A computer-generated execution of the melody

Additionally, MedMel offers advanced customization options for visualizing the edition and provides tools for music analysis, such as the search and compare tools.

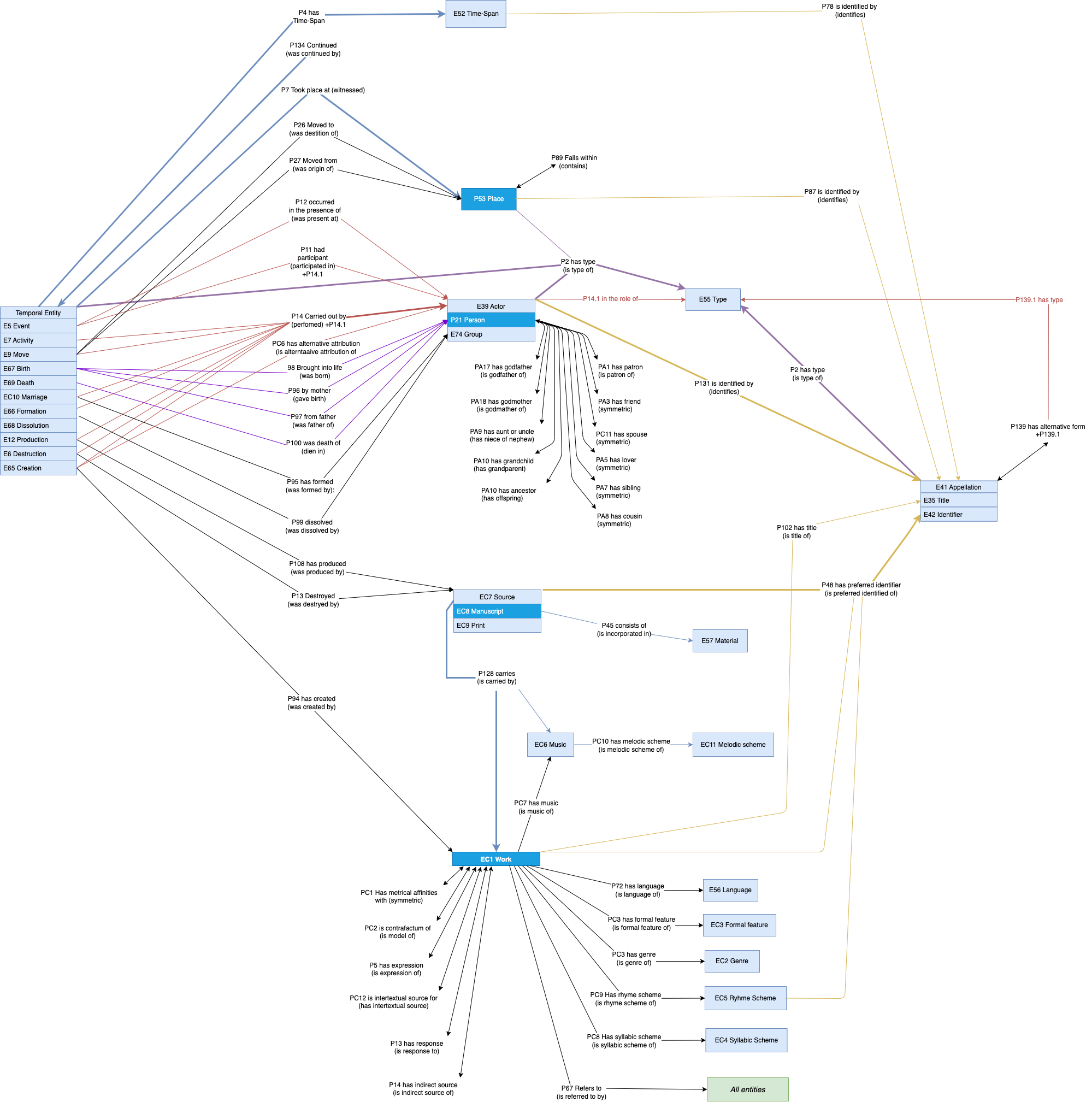

The onthology

MedMus data model implements an extended version of the CIDOC-CRM especially crafted for medieval literary and musical works.

Principal investigator: Stefano Milonia (University of Warwick)

Collaborators: Samuele Maria Visalli (Università di Roma Sapienza), Ermes Faillace (Università di Roma Sapienza), Giulia Boitani (University of Cambridge).

Contact: stefano.milonia[at]gmail.com